THE BIAK MASSACRE CITIZENS TRIBUNAL

University of Sydney, 6 July 2013

OPENING STATEMENT

I appear with Gustav Kawer of West Papua, recipient in Amsterdam of the “Lawyers for Lawyers” award for 2013, to assist the Tribunal.

Mr Turnbull SC and Mr O’Gorman SC appear also and will make submissions in due course – I shall return to that matter later.

Fifteen years ago today – 6 July 1998 – a massacre was taking place. It was 15 years ago to the date, if not the day – it was a Monday. The massacre took place in the dawn hours and later during the day. It was carefully planned and executed by Indonesian security forces in response to indigenous leaders who were using tactics of peaceful protest and non-violent civil disobedience.

Indonesia’s former President, Suharto, had been forced out of office by a popular uprising in May 1998. The people of West Papua (then “Irian Jaya”) began channeling this democratic energy in a new direction. Hundreds of peaceful West Papuans took to the streets of many towns in July 1998, demanding that the Indonesian government give them the opportunity to vote on the issue of independence which, to their minds and the minds of right-thinking persons everywhere, had been wrongfully denied them between 1963 and 1969.

In 1963 pursuant to an agreement made the year before, the Dutch had handed control of West Papua to Indonesia. After much agitation, a fraudulent “Act of Free Choice” in 1969 gave sovereignty to Indonesia. But the people of West Papua did not accept that and continued to agitate for a genuine democratic choice.

On 1 July 1998 in West Papua’s capital city, Jayapura, hundreds of people occupied the regional parliament – dancing, singing and beseeching their elected officials to meet their demands for a vote on the issue of independence. The protests in Jayapura began to dissipate on 3 July after two students were shot by security forces on the nearby university campus. But other independence demonstrations were taking place at this time – in Sorong on the island’s western tip and in the highland town of Wamena. The Morning Star flag, West Papua’s banner of independence first raised in 1961, was raised in public places again for the first time in nearly four decades.

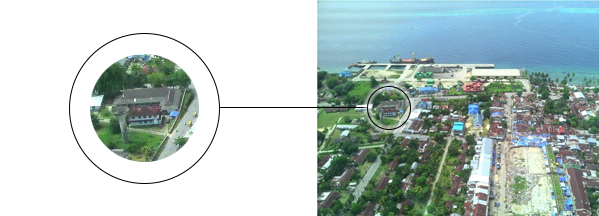

On the island of Biak, to the west of Jayapura, demonstrators occupied the harbor area of the town of Biak on Thursday 2 July, refusing to leave until the government met their demands. The occupation was started by the Deborah and Barak Prayer Group (“DEBAR”), a Christian group, singing and praying for progress towards independence. None of them was armed.

Filep Karma, a charismatic leader from an influential West Papuan family (and now an Amnesty International prisoner of conscience), came to lead this group. Filep was a civil servant in the Governor’s office in Jayapura who had been educated abroad, in the Philippines.

The Morning Star Flag was raised atop a water tower in the harbor of Biak just before dawn on 2 July. With the flag aloft, Karma urged those gathered – initially just several dozen people – to use peaceful tactics of resistance to get their message across.

( Today we will hear from Filep Karma, who is an Amnesty International prisoner of conscience. Human rights advocates smuggled a camera into his prison cell so that he could tell his story to the world.)

During the day the flag flying on the water tower began to draw larger and larger crowds. By noon hundreds, if not thousands, of people had gathered. Filep Karma urged the masses to: “defend the flag only using the Bible and hymns as weapons”. He told the crowd: “Indonesian law states that security personnel or police can let bullets fly if their life is at risk. If we are only armed with the Bible and hymns then the police will not shoot us”.[i]

At 2:30 that afternoon, a joint police and military operation attempted to disperse the crowd at the base of the water tower. They launched canisters of tear gas into the crowd with no apparent effect. When a low-ranking police officer, a Second Class Sergeant, beat an elderly demonstrator named Thonci Wabiser, the crowd spontaneously retaliated, destroying a truck belonging to Indonesian security forces. During this confrontation thirteen members of the security forces sustained injuries. Two of these men, who were reportedly in a critical condition, were evacuated to Java for medical treatment. It is understood that one of them died. The security forces eventually retreated and, for the time being, left the demonstrators at the base of the water tower in peace.[ii]

Quoting the Human Rights Watch Report of December 1998

“From July 2 to July 6, when the military opened fire, the morning star flag flew over the thirty-five-meter-tall water tower near the harbor in Biak town…people gathered beneath it, shouting freedom slogans, singing songs and dancing traditional dances. Some had painted their faces and

arms with the morning star symbol, and as the demonstration continued, many people in the immediate area joined in. The water tower is near both the main taxi terminal and a major market, so the site is one that many people would pass as part of their daily lives. Small boys reportedly guarded the area wearing armbands that said “Satgas [task force] OPM” (1998: 6).

The occupation continued for several days with some contacts between the demonstrators and officials, but with no violence.

“At 1:00 a.m. on July 4, the local military brought nine village heads together to discuss a strategy for attack, and both the subdistrict head (camat) and the subdistrict military commander told the village heads that each man was responsible for bringing thirty men into the city. He also told them that the district commander’s instructions were that each man should bring a weapon of some sort, whether a spear, a knife, or some other sharp object” (1998: 8).

Various negotiations continued during 4 and 5 July. On 4 July a Hercules aircraft brought troops from the Trikora regional command to Biak with anti-riot forces from the police mobile brigade.

On Sunday 5 July there were further negotiations after Sunday services. Then:

“The long-awaited attack took place at 5:00 a.m. on July 6. Troops from Battalion 733 Pattimura, stationed at the air force base at Manuhua aided local forces, and were reinforced by troops from two warships…The troops opened fire from four sides. Witnesses reported that five civilians who were already on the ground prone were deliberately shot. By 9:00 a.m., twenty-one

people had been brought to the hospital, one of whom, Ruben Orboi, died about an hour later in the hospital’s emergency room; he had been shot in the head. (A month later, his body had still not been turned over to his family.)” (1998: 9).

Ruben’s death, but no other, has been admitted by Indonesian authorities. Filep Karma was shot in both legs. Indonesian authorities have admitted that some people were injured.

A nurse “told Human Rights Watch that when an army truck drew up to the hospital entrance with some of the wounded, the latter were just pushed off the truck” (1998:9).

“One young man who was in the crowd when the shooting started told Human Rights Watch that the army loaded people on trucks, dead, wounded, and unhurt, and headed for the outskirts of the town. When they reached the jungle, he and ten others were let off the truck, while the remaining wounded and dead were driven on… He was then picked up with the other survivors and taken to the navy headquarters, where he was held from July 6 to July 11 and repeatedly kicked and beaten” (1998:9).

Attacks by Indonesian authorities continued during the day on 6 July throughout the town of Biak. It is said that many people were taken to sea on two Indonesian naval ships, one with the number 534 painted on it.

Later:

“… thirty-three bodies of men, women, and children washed up on the shore of East and North Biak beginning on July 27. The Indonesian army claimed they were victims of the tsunami that struck Aitepe, Papua New Guinea on July 16. There were unconfirmed reports from local people that some of the bodies had their hands tied behind their backs, and one was wearing a Golkar T-shirt, giving rise to the belief that at least some of the bodies might be those of shooting victims… All were buried quickly…without proper autopsies, so the cause of death remains uncertain.

“Six bodies, including an adult male, three adult females, an adolescent girl, and a girl estimated to be about four years old, were found in East Biak on July 27 and immediately buried by security forces. The bodies were in poor condition, but police said that some were marked with a tattoo that resembled the letter “w”. Nine more bodies washed up the next day. Of the six found in Amini village, five were children (three boys and two girls), and one was an adult woman wearing a shell necklace. A body of a girl estimated to be about twelve years old was found in Nyampun, Orwer village, and two other headless bodies were found on Paidado island, near the villages of Pasi and Saribra…On July 29, the body of an adult male was found in Yobdi, North Biak, and that of a young girl was found near Wadibu, East Biak” (1998: 10).

Previous Investigations

Investigations by national and international human rights organizations after the events of early July 1998 were largely thwarted, or at least frustrated, by Indonesian authorities. Calls for a formal inquiry by the government and relevant international bodies have been ignored.

Citizens Tribunal

While the Human Rights Watch report and some individual reports by residents of Biak and others provide some information about the events of 6 July 1998, the victims and survivors of the Biak massacre and the people of West Papua generally deserve a more definitive account of what happened. Further, they deserve follow-up action that is capable of holding to account those responsible, whether by formal court proceedings or administrative action, and capable of recognizing appropriately the suffering of those who were victimized and their families.

This Citizens Tribunal, therefore, will act in some ways like a Coronial Inquest in the common law legal system which inquires into deaths. It is not bound by the rules of evidence and procedure that bind a court of law. It may inform itself by reference to any information that it considers reliable, with or without qualification, and it may make its own arrangements about the manner in which it will proceed.

The Tribunal will receive and act upon evidence and information about the events presented in various forms; it will make findings about the involvement of individuals and authorities; and it will make recommendations for further action that might be taken. The evidence and information will be provided in today’s hearing and by material posted on the website www.biak-tribunal.org

Evidence will be presented today in accordance with the timetable provided to you all (perhaps with some adjustments as to times, as required).

Four witnesses will give direct testimony – their firsthand accounts of the events.

Three witnesses will testify by videorecorded evidence.

Three will tell their story in documents that will be presented.

And, as I have said, other material will be available on the website and therefore able to be considered by our judicial participants in preparing their findings and recommendations for next Tuesday, 9 July.

As I have said and as you will have seen from the timetable and from arrangements here in the Tribunal, there are two other representatives present, Mr Turnbull SC and Mr O’Gorman SC. The citizens convening this Tribunal recognize that the interests of more than the residents of Biak and the victims and survivors of the events of 6 July 1998 are represented in these proceedings – the Government of Indonesia, the armed forces and police of Indonesia, the government officials and other functionaries in Biak at relevant times. Some invitations have been issued to participate in today’s events, but none has been accepted. In the circumstances it has been considered proper to enable alternative views of the events to be put forward for consideration by the Tribunal and that will be done by the two highly qualified and experienced defence Senior Counsel who will, in effect, play “devil’s advocate” in the absence of clients and instructions. They will do that not by cross-examining witnesses, but by submissions that will be made at the end of today’s proceedings in which they will present alternative views.

The first evidence that we shall hear comes from Filep Karma. This recording was made clandestinely in prison in Jayapura where he is an Amnesty International prisoner of conscience. Watch the video here or on vimeo